Introduction

Since my early days on 8-bit and Amiga systems, I had the privilege of watching friends, family and customers interact with their devices and with the software we were creating. I always learn something useful from these shared expectations and frustrations, and I do sometimes feel guilty for the state of our industry. As calls for help are increasingly shifting from “crapware” to “ransomware” [1], here is my list of tips to make using Windows a safer and better experience for everyday users, both at home and at work.

While a few of the references should be solid enough even for some of the more technically minded, this is aims to be a page I can refer friends and family to.

What Windows Version?

The other day, my dentist showed me his 3D imaging system, asking whether it was OK to still use Windows XP. Sure I said, it might work virtually forever, as long as you keep it isolated (no internet, no untrusted software or USB keys, etc.)

If you have to use an older version of Windows like XP, my advice is to invest some time to put it into a virtual machine (Hyper-V or similar), which allows for long-term preservation and offers enhanced isolation and the possibility to more easily revert to a previous state. If your primary PC still uses Windows XP (or Windows Vista), and it is connected to the internet, then stop now and change that, because no third-party firewall or antivirus application can guarantee you a safe and smooth experience.

If you are using Windows 7-10 you are in much better hands. Since there are supported ways to do a free upgrade to Windows 10 even after the official July 2016 expiration (e.g. via the Assistive Technologies Offer), consider doing it sooner rather than later. Were it not for the forced reboots with loss of unsaved data when you leave the desk to grab a quick coffee, the disappearance of the Recent Items entry in the Start menu and the inconsistent style of its many user interface layers, I would say that Windows 10 is better than Windows 7 in all respects. It still is the best Windows version ever, and it will be supported for a long time.

If you are going to install from scratch, use a 64-bit version of Windows (which is a bit more robust also in terms of security) rather than a 32-bit one (which can’t be upgraded to 64-bit later).

Uninstall Flash and Java

Flash, together with Java, consistently tops the lists of security vulnerabilities that are exploited by malware as we browse the web or otherwise handle untrusted content.

The biggest loss you may experience by uninstalling Flash is that some older sites may not show some video content. Also thanks to Apple’s iOS being a precursor to not supporting Flash, well-designed sites have been offering the same content using HTML5 technologies for years.

If you absolutely need to use Java (e.g. I am aware of some ancient e-government apps), either you know what you are doing (in which case you will keep it always updated), or you should do that from the safety of a virtual machine.

So if you want your system to become lighter and safer with only a few clicks, go to the Control Panel, look for Flash or Java in the list of installed Programs, and uninstall them. If there are multiple entries, roll back from the newer ones to the older ones.

(Note that Java and JavaScript are two different things: I am recommending that you uninstall Java, not that you disable JavaScript in the browser settings.)

Update, Update, Update

It is “Patch Tuesday” as I am writing this, and like every second Tuesday of the month Microsoft and others released their latest wave of security updates.

If you are not sure whether your system is up to date, start Windows Update from the Control Panel (or Update & security in the newer Windows 10 Settings), and run a manual check. Install all updates and service packs it finds, except for optional addons you may not need, like Windows Live Essentials and Microsoft Silverlight.

You will also want to approve any updates for third-party essentials like Adobe Acrobat. Browsers like Firefox or Chrome update themselves automatically nowadays, but you should allow them to restart if prompted.

The reason why some of my non-technical friends don’t install Flash or Java updates is that they are afraid of doing something wrong. It’s OK to be careful, but there is a short list of common applications (and malware targets), which should be updated no matter what. These include Acrobat, Flash and Java (unless you do like I did, and uninstalled both Flash and Java a long time ago).

Unfortunately you get what you pay for with some free apps, so be careful as some update installers prompt you for more choices until they get what they want. Remember when you opted out of that “Free Search Bar!” that was offered when you installed your favorite PDF utility? Well, you should carefully keep that choice in mind with each update, because the installer may conveniently forget about it.

An example of such distrust-inspiring behavior comes from Microsoft’s own Skype, as its updater tries to reset the browser homepage and default search engine with each and every installation.

Sure, you can try and ask once, but is it OK to “forget” about the previous choice with each update? I think that this reduces consumer confidence in updates (remember why some people are afraid of going ahead with updates?), as well as setting a bad precedent for third parties. Respect of all previous setup choices should be part of Windows logo and marketplace requirements.

Sure, you can try and ask once, but is it OK to “forget” about the previous choice with each update? I think that this reduces consumer confidence in updates (remember why some people are afraid of going ahead with updates?), as well as setting a bad precedent for third parties. Respect of all previous setup choices should be part of Windows logo and marketplace requirements.

Malware Basics

Don’t expect any more Microsoft bashing from me now, because I actually believe that Microsoft’s Windows Defender (formerly Security Essentials) is a good antimalware (antivirus, antispyware) application. Being free it’s one of those rare cases where paying more doesn’t necessarily give you more. You also don’t have to worry about subscription renewals.

I recommend it not only because it plays nicely with the system without widening the attack surface, as others do [2], but also because the health of the Windows ecosystem is by definition a top priority for Microsoft. There is no conflict of interest, whereas it could be argued that some third parties benefit from sales of antivirus subscriptions, and there is a temptation of amplifying lists of items “found” and other fearsome details.

An expired antivirus application is not much better than no defense at all, so it should be uninstalled. Similarly, running two or more antivirus applications at the same time may create issues without achieving the desired protection. As antimalware applications share limitations in heuristic and other mechanisms, ultimately an informed and defensive user mindset (like following some of these tips) is what helps raise the security bar to the highest levels.

While I would prefer to use no antivirus at all, I too may occasionally run an additional one-time scan by booting with an independent tool, based on specific needs, for example if a system has already been compromised. Since originally writing this, Microsoft added a new Windows Defender Offline feature to Windows 10. It can be found under Settings/Update & security/Windows Defender. That too is a good tool to use from time to time.

Once, a friend was insisting that a specific “tool” was the only one that would find his constantly reoccurring “malware”, until we agreed that he had simply found exactly what he had been looking for on the internet. So, be careful with what you search for, as a download from an untrusted source may make matters worse, instead of delivering a solution.

Lastly, beware of “registry cleaners”, “download accelerators” and other utilities that promise wonders at no cost. These are the modern equivalent of snake oil, and should be avoided. If it was either necessary or easy to “clean” the registry, it would have been done by Windows. The best way to make the system faster and lighter without disrupting functionality or privacy is to not install certain types of software. I would also avoid any app that tries to install browser addons and other advertising-related tools.

Resist the Dumbing Down

If you followed the tips up to this point, you have a good version of Windows and you already significantly reduced the attack surface used by the most frequent exploits.

Are you willing to go the extra mile and learn some new things about files and Windows access control mechanisms? Then you can decide for yourself how to use that information, and whether you like the fact that as a user you are increasingly being shielded from these details, limiting your potential to learn and improve, without getting any extra protection in return.

Some versions ago it was decided that Windows should hide file name suffixes (endings like .txt, .pdf, .png, .mp3, .exe, etc.) In this simplified world model, users would no longer need to know that file suffixes even existed, or that they could be associated to a default file opening action, nor could even the most informed people appreciate the risk of something named “Virus.txt.exe” (which indicates an executable, not a text file), as that danger-revealing “.exe” part would be hidden.

You can undo this damage by going to the Folder Options and unchecking View/Hide extensions for known file types. Similarly, in the View tab of Windows 10’s File Explorer toolbar, you can check File name extensions. This won’t make anyone a computer expert in no time, but it encourages transparency and education, rather than preventing it.

Already back in the 1990s, the Amiga and Mac operating systems both had mechanisms whereby file types could be recognized by their content in addition (or in alternative) to their suffix. Even in modern Windows, there are XML-based file formats such as .docx and .rp9 where information inside the file provides further hints at what applications should best process the data. So, there is not an absolute rule that file suffixes universally describe the content and the opening application. However, they have been effective at this for decades, even on systems where this is not a requirement. Even if that wasn’t the case, there is no reason to hide parts of a file name, especially as Windows has two additional levels of protection from accidental suffix renames (one is the default selection that is set to the file name minus the suffix, and the other is a warning dialog if you change the suffix).

Don’t Run that File

Now you should be able to visually recognize PDF files from their .pdf suffix, potentially dangerous executables from the .exe ending, etc., but what about less common suffixes, like .spf? Any suffix that you are unfamiliar with is something you would have to research online.

Or, you may ask, why isn’t there some universal access control mechanism whereby Windows doesn’t even run something that you (or an administrator) haven’t deemed safe to install? There is, and it comes in the form of “Software Restriction Policies” and “Parental Controls”. These features allow the system to be configured so that it will only run executables installed by an administrator inside directories that were meant to run executable code (“Program Files”, etc.), where no code can be added by non-administrators. The rules can further be refined so as to only allow the execution of digitally signed code. Taken together, these settings raise the bar in a way that leaves little margin for situations where unauthorized code is run by mistake by everyday users.

For some reason, these great features are not enabled by default in Windows. However, there is no excuse for not having them enabled at least in a corporate environment. Should your IT staff ever ask “Why did you run that attachment?”, you might as well ask them “Why did you not enable Software Restriction Policies?”

UAC Is Good

The latest versions of Windows are especially effective at shielding users [3]. However, this protection only works as long as you don’t run code with administrative privileges.

This means that you should not ignore (or disable) those Windows “UAC” (User Account Control) prompts, i.e. those requests that darken the area all around the dialog. When they pop up while you are updating a trusted application, it is generally safe to approve the request. Otherwise, you should think at least twice, because you are about to give special permissions to some potentially untrusted code. This may even occur unintentionally if you are working with administrator user privileges, and you disabled the UAC system option because you found it to be “annoying”.

Most malware is able to penetrate an otherwise well-maintained system because of a brief lapse of this rule. Once you allow some unknown code (e.g. something “found” on a USB stick) to run with administrative privileges, you can’t be sure that your system is yours anymore.

Ransomware

“Ransomware”, i.e. malware that encrypts your data and then asks for money to decrypt it, is actually the reason that made me want to share these notes. I hear it happen all around me. It is one of those things that makes me feel bad for the state of this industry, and also for the non-technical people who get bashed by their IT department, who often could instead have prevented it.

In a majority of cases, we are all able to recognize something as inappropriate, but sometimes an email with the right subject manages to slip through at exactly the right time, maybe when we were expecting an account statement, or a courier, and that’s when disaster may strike.

If I had reason to believe that my system had been compromised by some “ransomware”, I would unplug the network cable and hibernate or shut down the system, before more damage occurs. First though, if there was a specific message demanding payment, I would take a photograph of it (you can’t completely rely on a screenshot, as that too could be lost). Hibernation may have some advantages, in that it could help preserve details stored in memory that could later aid in a decryption.

Then, consider paying. Or at least, don’t delete the payment instructions, nor the encrypted files. You might change your mind later, or a free recovery tool might become available [4]. Even law enforcement agencies like the FBI advised to consider payment, if the data is important. After all, a bitcoin isn’t that steep a price to pay. In any case, should you decide to restore the system on your own, you should make a copy of the encrypted data, for possible future recovery.

Online, Offline and Travel

Do you consider yourself or your work important enough to be the possible target of an aimed attack? If so, my advice is to work on two different systems: a “vulnerable” one, connected to the internet, and another more secure system, which should be offline at all times. If it feels almost like wearing a tinfoil hat, I can only agree.

At the same time, you might benefit from two systems anyway:

- A PC for offline work (distraction-free productivity?), a notebook for online work

- You can carry the notebook with you when traveling

- One can be the backup of the other (for productivity applications, not for long-term data storage, which should be covered via backups)

In this scenario, a light notebook could act as both the “internet computer” and the “travel computer”. Since this system would be at higher risk of theft of exposure anyway, it makes sense for it not to be a container of sensitive data. It could be set up to only store a limited period of email history locally, and to access more important data only via a secure connection, which needs to be authorized via a password, smart card or other secure mechanism.

If you travel a lot, a situation that may leave you with mixed feelings even more than a stolen notebook or phone is that at customs you are asked to hand over your devices, providing your fingerprint or other access credentials. This has been happening for years in countries we associate with democracy and freedom (Canada, Israel, United Kingdom, United States, etc.), even on arrivals by train. If you don’t comply, you might be denied entry, or even arrested. I consider myself an “I don’t have anything to hide” person, but I admit that I am not totally comfortable with this scenario. While I see it as a necessary annoyance to contrast some crimes ranging from child pornography to terrorism, I am also concerned with what else may happen with this data, perhaps years into the future.

As our devices increasingly become our mind extensions, will our habits change in the way we cross jurisdictions? Will our future nakedness be one of travels without devices, or one where everyone may read into those devices (and perhaps our minds)? I don’t know the answer, but it makes me think about that tinfoil hat…

Post Scriptum

As of May 2017, a massive wave of ransomware known as “WannaCry” or “WannaCrypt” has been making the rounds. It exploits a vulnerability that had been addressed by Microsoft (KB4012598) in the March 2017 “Patch Tuesday”. Systems that ran Windows Update since then would not have been affected.

While it originally seemed that there were no such updates for Windows XP and Windows Server 2003, which are outside of the normal support timeframe, Microsoft later also made available the KB4012598 updates for these older systems. If you are still running one of these Windows versions, you can download the update here.

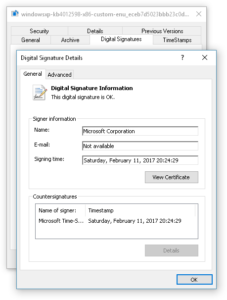

Interestingly, the updates that were released to the public in May 2017 had been finalized already on February 11, 2017:

References

1. Ransomware: Past, Present, and Future

Cisco Talos Blog, 2016

2. Joxean Koret

“Breaking Antivirus Software”

44CON, 2014

3. Vasily Bukasov and Dmitry Schelkunov

“Under the hood of modern HIPS-es and Windows access control mechanisms”

Defcon Russia 2014 (DCG #7812)

4. Lawrence Abrams

TeslaCrypt shuts down and Releases Master Decryption Key